"First of all, it's really beautiful. And it's teeming with galaxies," said JWST operations scientist Jane Rigby at the July 12 briefing. "That's true of every image we've taken with Webb. We can't imagine a blank sky. Everywhere we look, there are galaxies."

Going deep

The galaxies seen in the first published image lie behind a cluster of galaxies about 4.6 billion light-years away. The mass of these closer galaxies distorts space-time in a way that magnifies the objects behind the cluster, allowing astronomers to peer more than 13 billion years into the early days of the universe.

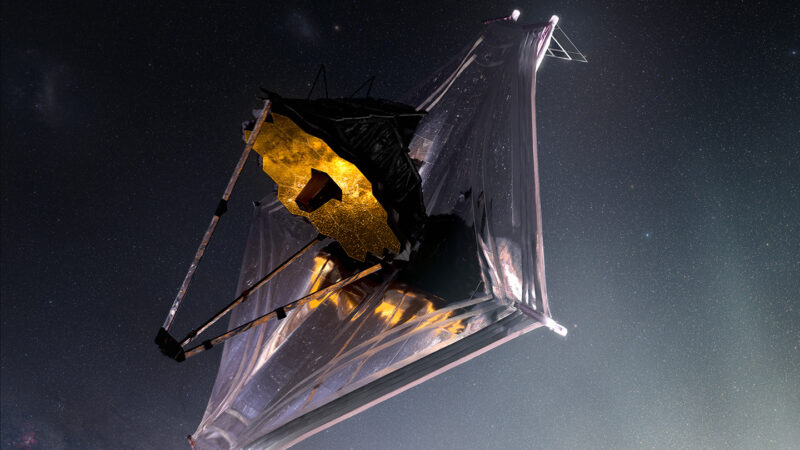

Even with this celestial support, other existing telescopes could never see that far. But the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, is incredibly large - at 6.5 meters, its mirror is nearly three times as wide as that of the Hubble Space Telescope. It is also seen in the infrared wavelengths of light, where distant galaxies appear. These features give it an advantage over earlier observatories.

"There's a sharpness and clarity that we've never had before," says Rigby of the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, MdL, NASA. "You can zoom in and play around."

Although this first image represents the deepest view yet into the cosmos, "this isn't a record that will stand for long," said astronomer Klaus Pontoppidan of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore at a June 29 news conference. "Scientists will very quickly surpass this record and go even deeper."

But JWST wasn't built just to look deeper and farther into the past than ever before. The first images and data show scenes from near and far space, glimpses of individual stars and entire galaxies, and even a look at the chemical composition of a distant planet's atmosphere.

"These are images taken over five days. Every five days we get more data," Mark McCaughrean, science advisor to the European Space Agency, said at the July 12 press conference. (JWST is an international collaboration between NASA, ESA, and the Canadian Space Agency.) "It's the culmination of decades of work, but it's only the beginning of decades. What we've seen today with these images means we're ready now."

Cosmic Cliffs

This image shows the "Cosmic Cliffs," part of the vast Carina Nebula, a region about 7,600 light-years from Earth where many massive stars are born. Some of the Hubble Space Telescope's most famous images show this nebula in visible light, but the JWST shows it in an "infrared blaze," Pontoppidan says. The JWST's infrared detectors can see through the dust, so the nebula appears particularly littered with stars.

"We're seeing new stars that were completely hidden from us before," says Amber Straughn, an astrophysicist at NASA Goddard.

But the molecules in the dust themselves are also glowing. Energetic winds from the baby star at the top of the image push and shape the wall of gas and dust that stretches through the middle. "We see examples of bubbles, voids, and jets blown out by newborn stars," Straughn said. And gas and dust are the raw material for new stars - and planets.

"It reminds me that our sun, planets, and ultimately ourselves were formed from the same material we see here," Straughn said. "We humans are connected to the universe. We made up of the same stuff."

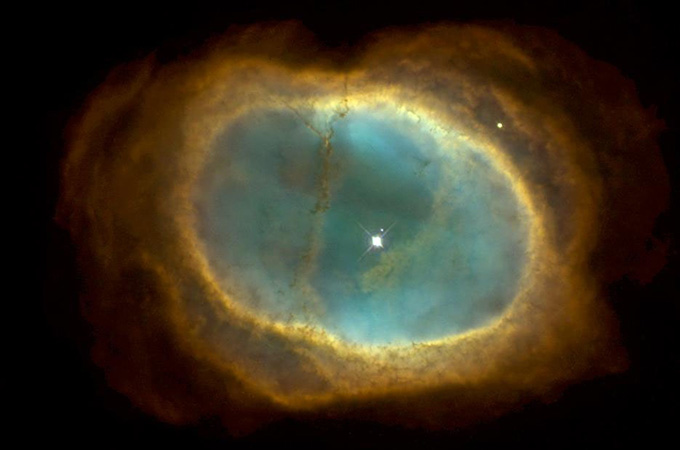

Foamy nebula

The Southern Ring Nebula is an expanding cloud of gas surrounding a dying star about 2,000 light-years from Earth. In earlier Hubble images, the nebula looks like an elongated swimming pool with a fuzzy orange deck and a bright diamond white dwarf star in the center. JWST extends the view far beyond that, revealing more tendrils and structures in the gas than previous telescopes could detect.

"You see this bubbling, almost foamy look," says JWST astronomer Karl Gordon of the Space Telescope Science Institute. In the left image, which captures near-infrared light from JWST's NIRCam instrument, the frothing is due to molecular hydrogen formed as the dust expanded away from the center. The center appears blue due to hot ionized gas heated by the star's remnant core. Rays of light escape the nebula like the sun shining through patchy clouds.

In the image at right, taken by the mid-infrared camera MIRI, the outer rings appear blue, indicating hydrocarbons forming on the surface of dust grains. The image from MIRI also shows a second star in the nebula's core.

"We knew it was a binary star, but we didn't see much of the actual star that created this nebula," Gordon said. "At MIRI, that star is now glowing red."

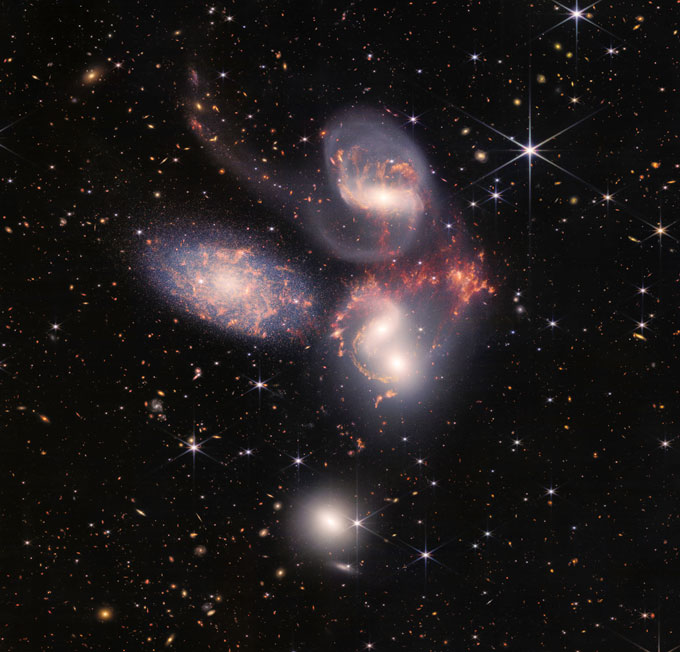

A galactic quintet

The Stephen's Quintet is a group of galaxies at a distance of about 290 million light-years, discovered in 1877. Four of the galaxies are in an intimate gravitational dance, with one member of the group passing through the nucleus of the cluster. (The fifth galaxy is much closer to Earth and appears only at a similar location in the sky.) The JWST images show more structure within the galaxies than previous observations and reveal where stars are born.

"This is an essential image and area of studies" because it shows the kinds of interactions that drive galaxy evolution, said JWST scientist Giovanna Giardino of the European Space Agency.

In the instrument's image alone, MIRI, the galaxies look like wispy skeletons moving toward each other. Two galaxies are clearly on the verge of merging. And in the up universe, evidence of a supermassive black hole can be seen. Material swirling around the black hole is heated to extremely high temperatures and glows in infrared light as it falls into the black hole.

The sky of an exoplanet

This "picture" is quite different from the others but is no less exciting scientifically. It shows the light spectrum of the star WASP 96 as it passes through the atmosphere of its gas giant planet WASP 96b.

"You see a bunch of things that look like bumps and wobbles to some people, but they're full of information," says NASA exoplanet scientist Knicole Colón. "You see bumps and wobbles that indicate the presence of water vapor in the atmosphere of this exoplanet."

The planet is about half the size of Jupiter and orbits its star every 3.4 days. Previously, astronomers assumed it had no clouds in the sky, but the new data from JWST show signs of clouds and haze. "There are signs of clouds and haze because the water spots aren't as large as we predicted," Colón said.

A long time to wait

There's been a long wait for these first images and data. The telescope that would become the JWST was first conceived in the 1980s, and planning and construction suffered years of budget problems and delays (SN: 10/6/21).

The telescope was finally launched on December 25. It then had to deploy and assemble in space, travel to a gravitationally stable location about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, align its insect-like primary mirror of 18 hexagonal segments, and calibrate its scientific instruments (SN: 1/24/22). There were hundreds of possible sources of error in this process, but the telescope successfully unfolded and began its work.

"We're thrilled that it's working because there was so much at stake," said John Mather, lead scientist for the JWST project from Goddard Space Flight Center NASA. "The world trusted us to put our billions into this project and make it work, and it's working. So it's a great relief."

In the month that followed, the telescope team released its first images from the calibration, which already showed hundreds of distant galaxies never before seen. But the images released now are the first full-color images created from the data that scientists will use to begin unlocking the mysteries of the universe.

"You see things that I never dreamed were out there," Mather says that relief for the telescope was palpable if finally seeing the first enable. "It was like, 'Oh my God, we did it,'" says image editor Alyssa Pagan, also of the Space Telescope Science Institute. "It seems impossible. It's like the impossible happened."

Given the anticipated anticipation of the first images, the imaging team was sworn to secrecy. "I couldn't even tell my wife about it," says Pontoppidan, leader of the team that created the first color science images.

"You're looking at the deepest image of the universe yet, and you're the only one who's seen it," he says of the first image, released July 11. "It's profoundly lonely." In but a short time, the team of scientists, image editors, and science journalists have seen something new every day for weeks as the telescope downloaded the first images. "It's a crazy experience," Pontoppidan says. "Once in a lifetime."

For Pagan, the timing is perfect. "It's a very unifying thing," she says. "The world is so polarized right now. I think it could use something a little more universal and unifying. It's a good perspective to be reminded that we're part of something so much bigger and beautiful."

The JWST is just getting started, as it now begins its first round of mostly science operations. "There's a lot more science to be done," Mather says. "The mysteries of the universe aren't going to end anytime soon."

You must be logged in to post a comment.