Researchers believe they have discovered the origins of the Black Death, more than 600 years after it killed tens of millions in Europe, Asia and North Africa.

The mid-14th Century health catastrophe is one of the most significant disease episodes in human history.

But despite years of research, scientists had been unable to pinpoint where the bubonic plague began.

Now analysis suggests it was in Kyrgyzstan, Central Asia, in the 1330s.

A research team from the University of Stirling in Scotland and Germany's Max Planck Institute and University analyzed ancient DNA samples from the teeth of skeletons in cemeteries near Lake, in Kyrgyzstan.

They chose the area after noting a significant spike in burials there in 1338 and 1339.

Dr Maria, a researcher at the University, said the team sequenced DNA from seven skeletons.

They analyzed the teeth because, according to Dr Maria, they contain many blood vessels and give researchers "high chances of detecting blood-borne pathogens that may have caused the deaths of the individuals".

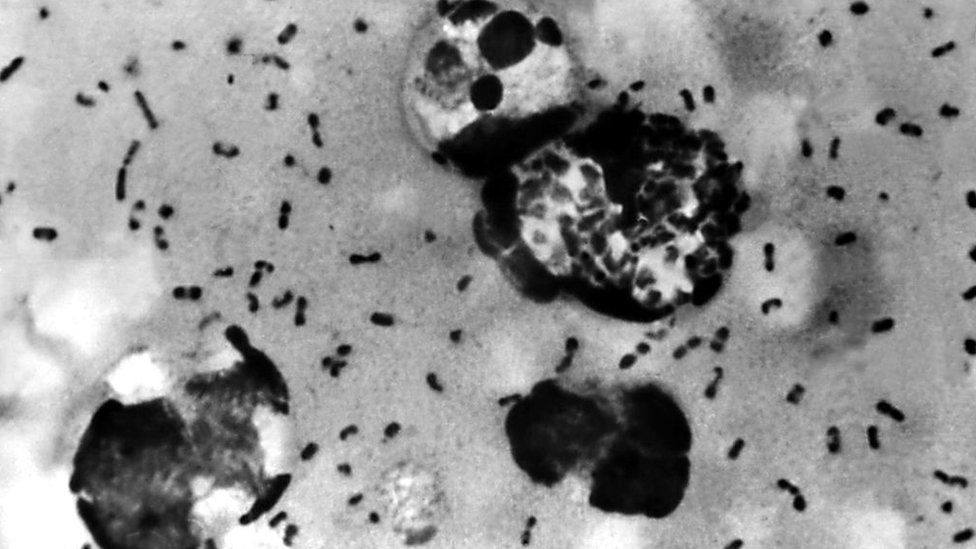

The research team were able to find the plague bacterium, Yersinia, in three of them.

- Black Death 'spread by humans not rats'

Dr Philip, a historian at the University of Stirling, said of the discovery: "Our study puts to rest one of the biggest and most fascinating questions in history and determines when and where the single most notorious and infamous killer of humans began."

The research does have some limitations - including the small sample size.

Dr Michael Knapp from the University in New Zealand, who was not involved in the work, praised it as "really valuable", but noted: "Data from far more individuals, times and regions... would really help clarify what the data presented here really means."

The researchers' work was published in the journal Nature, titled "The source of the Black Death in fourteenth-century central Eurasia".

What is bubonic plague?

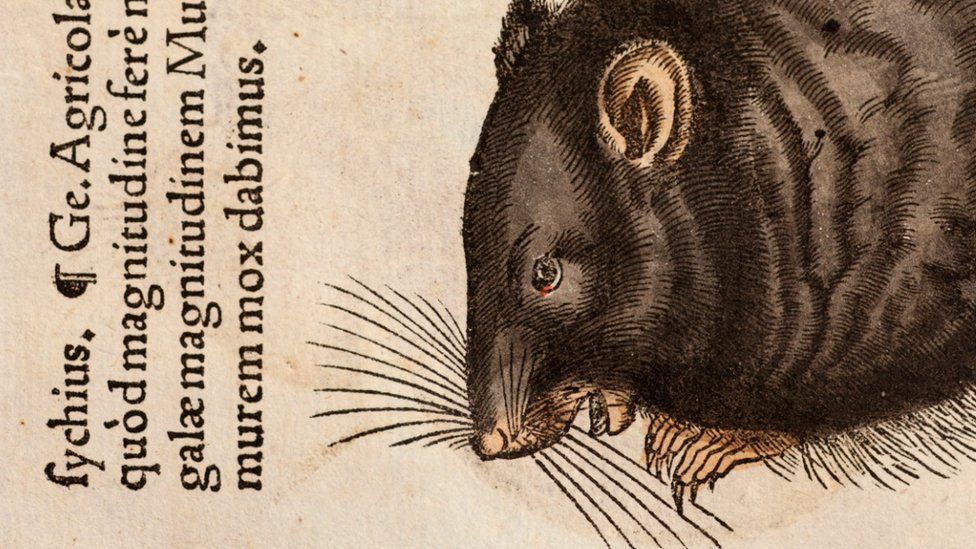

Plague is a potentially lethal infectious disease that is caused by bacteria called Yersinia that live in some animals - mainly rodents - and their fleas.

Bubonic plague is the most common form of the disease that people can get. The name comes from the symptoms it causes - painful, swollen lymph nodes or 'buboes' in the groin or armpit.

From 2010 to 2015, there were 3,248 cases reported worldwide, including 584 deaths.

Historically, it has also been called the Black Death, in reference to the gangrenous blackening and death of body parts, such as the fingers and toes, that can happen with the illness.

Black Death 'spread by humans not rats'.

Rats were not to blame for the spread of plague during the Black Death, according to a study.

The rodents and their fleas were thought to have spread a series of outbreaks in 14th-19th Century Europe.

But a team from the universities of Oslo and Ferrara now says the first, the Black Death, can be "largely ascribed to human fleas and body lice".

The study, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, uses records of its pattern and scale.

The Black Death claimed an estimated 25 million lives, more than a third of Europe's population, between 1347 and 1351.

"We have good mortality data from outbreaks in nine cities in Europe," Prof Nils Stenseth, from the University of Oslo.

"So we could construct models of the disease dynamics."

He and his colleagues then simulated disease outbreaks in each of these cities, creating three models where the disease was spread by:

- Rats.

- Airborne transmission.

- Fleas and lice that live on humans and their clothes.

In seven out of the nine cities studied, the "human parasite model" was a much better match for the pattern of the outbreak.

It mirrored how quickly it spread and how many people it affected.

"The conclusion was very clear," said Prof Stenseth. "The lice model fits best."

"It would be unlikely to spread as fast as it did if it was transmitted by rats.

"It would have to go through this extra loop of the rats, rather than being spread from person to person."

'Stay at home'.

Prof Stenseth said the study was primarily of historical interest - using modern understanding of disease to unpick what had happened during one of the most devastating pandemics in human history.

But, he pointed out, "understanding as much as possible about what goes on during an epidemic is always good if you are to reduce mortality".

Plague is still endemic in some countries of Asia, Africa and the Americas, where it persists in "reservoirs" of infected rodents.

According to the World Health Organization, from 2010 to 2015 there were 3,248 cases reported worldwide, including 584 deaths.

And, in 2001, a study that decoded the plague genome used a bacterium that had come from a vet in the US who had died in 1992 after a plague-infested cat sneezed on him as he had been trying to rescue it from underneath a house.

"Our study suggests that to prevent future spread hygiene is most important," said Prof Stenseth.

"It also suggests that if you're ill, you shouldn't come into contact with too many people. So if you're sick, stay at home."

You must be logged in to post a comment.